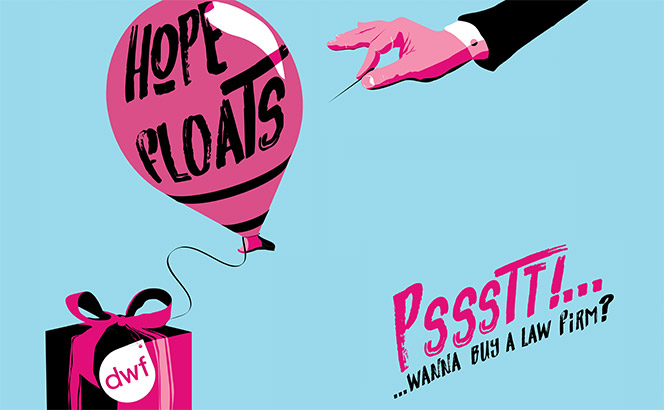

In July, the board of DWF Group Plc confirmed market reports that it was planning to delist from the London Stock Exchange in a buyout by private equity firm Inflexion. Having floated in 2019, the fanfare of a record £95m IPO and a valuation of £366m to make DWF the UK’s largest listed law firm has arguably not lived up to the hype.

In the four years since, the firm’s fortunes have been chequered, with its highest valuation recorded just before the pandemic hit at 141.4 pence per share in February 2020, with a drop to 90 pence per share in March 2020 and an all-time low in June 2020 of 53 pence per share.