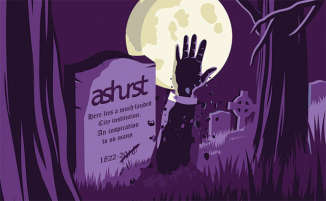

Sometimes in institutional terms, something has to die before something new can live. The good news for Ashurst, as chronicled in this month’s cover feature, is that the City player is showing vivid signs of renewed life, with the firm set to post by far its best performance after a decade that has been plain bad. After the low points in late 2016 and early 2017, level-headed people were asking how long this could continue before decline became outright calamity.

The obvious caveat – and it is a substantial one – is that this has come largely by building on the ruins of what Ashurst was: a storied, corporate-driven City player with enviable history and a cohesive culture. What has emerged as the old edifice progressively crumbled is unrecognisable against Ashurst circa 2009. Thanks to its controversial merger with Blake Dawson, the shape and practice mix of the business has radically changed. Its once-vaunted private equity team has been battered down to functional coverage across Europe – the final blow to any borderline claim to first-division status being Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer’s five-partner Paris raid two years ago. And most of the big-name corporate figures have left over the years or retired – most recently Robert Ogilvy Watson and Simon Beddow – leaving a core corporate practice generating around 20% of its income; on paper, you would expect a firm of this heritage to be doing over 30%.

And what has emerged? I am not saying Ashurst is now a huge infra boutique, but it is doing about as good an impression of one as you can imagine for a firm that until recently saw itself as a Magic Circle challenger. Look at its litigation, corporate and finance teams, and you will see a lot of work for infra and energy clients. The major exception to this has been the firm’s surprisingly successful move into the TMT sector, building in part on the 2016 hires of Nick Elverston and Amanda Hale from Herbert Smith Freehills.

Much of this revival obviously comes through making a virtue of necessity. Having failed to remain credible in executing its previous model, it has pivoted to something new. In these Brexit-infused times, Ashurst’s accepted view that it is where it is, and it was better to move forward constructively and play to new strengths than bemoan what it has lost, deserves praise. After all, moving on will be tough given its partnership’s historic addiction to angsting about the past.

It also speaks to the theme we touch upon in this month’s leader, which argues that major City firms cannot credibly continue as lookalike generalists. The less Ashurst resembles its peers, the easier it is to imagine the firm thriving, as has happened with its lean-but-effective US infra push. Much of the credit here has to go to managing partner Paul Jenkins. In an age in which many large City-bred law firms have forgotten the value of effective leadership, his clarity, competence and common sense has gone a long, long way.

I cannot fully commit yet – I have been hurt before. It will take another year or two of confident performance before the firm can genuinely lay claim to a credible place in the global market and I still argue its disputes team is too small for its business model. But it is a pleasure to see life in the old Ashurst yet.

See Inflection point for more on Ashurst.